Fourteen miles from Durban’s beautiful beaches and luxury hotels, lies an area as remote as Harlem is from Fifth Avenue. Here, in the hills of Natal, Mohandas K. Gandhi purchased 100 acres of land for 1,000 pounds. The bargain included a spring that flowed through the property, fruit trees, and a dilapidated cottage. The year was 1904, and the Indian lawyer had not yet made his mark upon the world.

Fourteen miles from Durban’s beautiful beaches and luxury hotels, lies an area as remote as Harlem is from Fifth Avenue. Here, in the hills of Natal, Mohandas K. Gandhi purchased 100 acres of land for 1,000 pounds. The bargain included a spring that flowed through the property, fruit trees, and a dilapidated cottage. The year was 1904, and the Indian lawyer had not yet made his mark upon the world.

Greatly influenced by the English critic John Ruskin’s essay, “Unto This Last,” which stated, “The good of the individual is contained in the good of all” and “A life of labor is the life worth living,” Gandhi moved his family, and those of his friends and co-workers, to the farm he named Phoenix. He transferred a printing press from Durban in order to continue publishing “Indian Opinion,” a newspaper with which he was deeply involved.

Young and old labored in the fields, worked on the press in their spare time, and got equal wages. There were no restictions on nationality, religion, or color, and everyone was welcome as long as he or she shared responsibilities.

The Indian leader had a strong love for children and believed in learning by doing. His own high standards of ethical conduct set an example for all to follow. Though well-meaning friends urged Gandhi to isolate his own sons from unruly boys on the farm, he refused. The barrister felt other boys could benefit by association with his children, who, in turn, would learn not to feel superior to others.

Gandhi’s original plan was to retire from his law practice and live at the settlement, doing manual labor, but demands on his time plus his talent for public work allowed him only brief respites on the farm he loved. His years in South Africa were productive ones, and it was in that country he developed “Satyagraha,” non-violent civil disobedience.

The Phoenix Settlement continued to grow long after Gandhi returned to help his homeland win independence from Great Britain. The ashram served as a model for later communities in both South Africa and India. Philosophies developed in those early years—equality, physical labor, search for truth—became standard.

In recent times, Ela Ramgobin carried on the work of her famous grandfather, establishing a community center in the once beautiful farm. Needy Indians were given food and healthcare as were their black neighbors from the slums of Inanda. A school building in memory of Kasturba, Mahatma Gandhi’s beloved wife, was made possible by donations from Transvaal Indians and a grant from the Natal Provincial Government, while the clinic was the result of contributions from the South African Sugar Industry, with aid from the University of Natal.

For almost one hundred thirty years, Indians tried to establish themselves as an integral part of South Africa. In 1961, Indians were acknowledged as “citizens,” though they were not permitted to vote. Black resentment against the 800,000 Asians grew stronger when Indians were granted a voice in the three-chambered Parliament under the new South African constitution, and the Africans were not.

Suddenly, on August 9, 1985, violence erupted. Angry black youths burned and looted the site where Gandhi had preached non-violence. The museum housing historical books and papers, Gandhi’s home, schools, and other buildings were gutted, while hoodlums carried off the Indian leader’s desk, chair, and personal belongings. Adjacent sugar fields were also set ablaze.

The clinic was saved only because an old African man remained there, imploring all who would listen, to spare the medical building so important to the blacks. Also saved from the ravages of the torch was the Shanti Girl Guide Center.

Indians who were present that night fled from the settlement. Most never returned.

The hills of Phoenix are now dotted by squatters’ shacks. Many are made from tree branches, insulated by empty milk cartons, and covered by mud. Some use automobile packing crates for walls, giving a nickname, “Toyota Township.” The new occupants are Black—not those who were responsible for the night of terror, but ones who want to improve their lot in life.

No rent is charged for living in the area, and there are signs that the residents are organizing. They want to get permission from the foundation that runs the historic site to restore the burned school building for their children.

In the meantime, facilitities that have no electricity, little furniture, and few school supplies are being utilized. Some of the younger students sit on bricks, as there are too few benches. Other children are in a shelter open on three sides because they have not yet received permission to use the locked buildings.

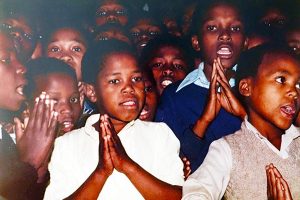

Five unpaid teachers serve more than three hundred students. Younger pupils are taught in Zulu or African languages while older ones learn English. The children seem eager to learn reading, writing, and arithmatic, as well as ethical conduct. At the end of the school day, they sing hymns and say prayers.

A bust of Gandhi graces the clinic that still plays an important part in the settlement. On one wall is painted a mural depicting the Indians’ contribution to South Africa’s sugar industry, while posters for preventative medicine are hung on the others. A nursing staff cares for walk-in patients.

People take pride in their new homes and can be seen clearing weeds from their gardens.

Though the younger people are unfamiliar with Mahatma Gandhi, they are living by the principles that once inspired him. Like the legendary bird Phoenix, for whom the founder prophetically named the farm, a new settlement is rising from the ashes of the old.

Reprinted from India West, October 2, 1987

Gandhi’s Spirit Lives on At Phoenix Settlement By Ellen Israel Goldberg