Getting my book into print took 32 years. I didn’t write continuously. I would have periods in which I would be inspired and others where I’d put the manuscript aside, sometimes for years. Life got in the way, so the creative juices didn’t always flow. I often worked long hours in business, with extra time for family and volunteering. Sometimes, there were a few minutes for relaxing.

Getting my book into print took 32 years. I didn’t write continuously. I would have periods in which I would be inspired and others where I’d put the manuscript aside, sometimes for years. Life got in the way, so the creative juices didn’t always flow. I often worked long hours in business, with extra time for family and volunteering. Sometimes, there were a few minutes for relaxing.

Meanwhile, I read many books, both fiction and non-fiction, especially biographies and “how-tos” for writing. I also took courses, including writing short stories or features, as well as photography, then joined a few writing clubs.

Ideas began to marinate. Every few years, I’d start again. Good advice from people who had read my manuscript was incorporated into each new rendition. In commercials, the famous actor Orson Wells would say, “…no wine before its time.” In my case, it was “no book before its time.”

I wrote articles for a number of publications, including Indo-American News, Jewish Herald-Voice, and even Houston Horse & Hound. Each time, I improved my craft. It was flattering to hear the instructor of the Advanced Feature Writing Continuing Education Class at Rice University say, “I learn something each time I read your articles.”

That’s one of my goals in writing these blogs: sharing information from the many interesting activities I’m privileged to attend. I’ve been afforded opportunities that bring me into contact with people from all walks of life, many countries, and a variety of beliefs. In a world that is becoming increasingly wary of “The Other,” we must find a way to communicate with those who don’t necessarily share our views.

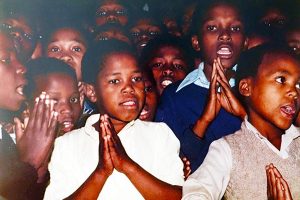

Some of my blogs will be reprints from articles I wrote in the past that will give an historic perspective of what was happening at the time. My visit to Gandhi’s first ashram in 1986 was one of those. South Africa was changing, and Apartheid was on its last legs.

My other goal is to encourage people to pursue their dreams. Never give up. There’s always hope. I’m a living example of that.

I’d like to hear from you, so please feel write. I’ll try to respond to each of you.

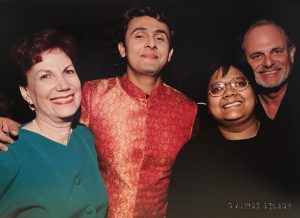

Sutapa Ghosh, my longtime friend who is a film producer and the Founder/Director of the Indian Film Festival of Houston, called one afternoon in 2003, asking, “Do you know a good lyricist?” She was leaving for India the next day to meet with the world-reknown Indian pop singer Sonu Nigam to discuss a music project with him.

Sutapa Ghosh, my longtime friend who is a film producer and the Founder/Director of the Indian Film Festival of Houston, called one afternoon in 2003, asking, “Do you know a good lyricist?” She was leaving for India the next day to meet with the world-reknown Indian pop singer Sonu Nigam to discuss a music project with him. Fourteen miles from Durban’s beautiful beaches and luxury hotels, lies an area as remote as Harlem is from Fifth Avenue. Here, in the hills of Natal, Mohandas K. Gandhi purchased 100 acres of land for 1,000 pounds. The bargain included a spring that flowed through the property, fruit trees, and a dilapidated cottage. The year was 1904, and the Indian lawyer had not yet made his mark upon the world.

Fourteen miles from Durban’s beautiful beaches and luxury hotels, lies an area as remote as Harlem is from Fifth Avenue. Here, in the hills of Natal, Mohandas K. Gandhi purchased 100 acres of land for 1,000 pounds. The bargain included a spring that flowed through the property, fruit trees, and a dilapidated cottage. The year was 1904, and the Indian lawyer had not yet made his mark upon the world.